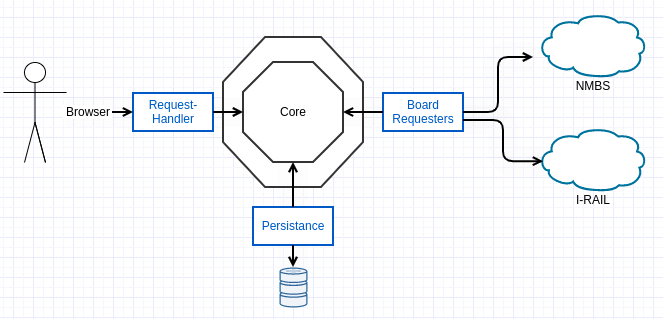

Hexagonal Architecture Example

The hexagonal architecture also known as ports and adapter architecture, is one of the most powerful design patterns that I know: it respects the open-closed principles, correct dependency flow, and it is a pragmatic approach to building software systems. The example application is a Java SpringBoot application that will collect all the Belgian train departures and create statistics about it. You can find the source code on GitHub.

Modules

Overview of the structure of the application.

The application consists of the following Java-modules:

Core

This module contains the model and the most important business rules.

The packages board, station, statistic, traindeparture contain the model, mappers, events, associated exceptions and interfaces for each aggregate.

This may look a bit like Package by feature, but it’s very handy to find all aggregate-related files together.

The services however are grouped in their own package called service and their you can find the real application logic:

- The logic of detecting a train departure in the

BoardHarvester - The ways to create daily/yearly statistics from the repositories in the

StatisticService

The big advantage of the organisation is that all the important code is bundled here in one beautiful package, so it truly is the heart of the application.

It has almost no dependencies, so it’s very easy to test and mock.

The only dependencies in the module are Spring (which can be moved to the application-module if wanted) or support libraries like Guava.

It also contains the interfaces for the other modules.

Take the example of StationRetriever that will fetch all the station for a certain country.

The core is not interested in how that exactly happens.

Is it being queried from a database?

Or is it a flat file that is being imported?

These are just details, that are not important for the business logic of the application.

The only concern of the core is that the interface is being called at certain moments during the execution of some services.

Persistence

The details of how the models are being persisted or retrieved are grouped in this module. In this application the choice was to use DynamoDB of AWS, a non-relational document store. DynamoDB has some nice features like it is cheap and really performant to query on a given range key, so perfect to gather statistics. If however another database is chosen, the only changes will need to happen in this module.

Sometimes there is not enough value to make a separate persistence module, like when your database model and core model are almost identical. In this case with the DynamoDB, the data model needs to have a lot of annotations and has a lot of noise and implementation details on how to persist. This means however that we need to provide extra mappers to translate the core model to a database model. Taking everything in account, it seemed the best choice.

BoardRequester

This module will implement all the details on how the train information will be fetched from external services.

There are two ways to do this: using the webservice of NMBS or the one of iRail and by coincidence both are REST-webservices.

To fetch the data safely, it’s needed to take in account the possible time-outs or other errors that the webservices may throw.

Luckily there are some awesome libraries like Hysterix with circuit-breakers that will help out a lot.

The only thing needed is the dependency, which is of course only interesting for this module, not the other ones.

RequestHandler

The interactions with the applications will happen with REST-calls coming from a frontend, so this module will be like the gate to the outside.

Since all the endpoints that the application offer are read only, a good suiting name would also be Projector: just exposing data.

In one of the earlier versions of this application, this module was a Vaadin-module: so it would collect the data and immediatly provide an user interface for it. The decision was made to abandon Vaadin for a more common Java backend - Javascript (Angular/Vue/React) frontend. Again the entire frontend could change without impacting any other modules.

Application

The final module is the glue that will take the loose modules together and combine them to one application. So basically it only has the Main-method with in this case the SpringBoot-Application annotation and the system properties. The big advantage of this module is that the compilation will lead to one jar-file for the entire application. It is also the perfect place for the integration tests that will use the entire application.

Events

Hexagonal architecture works also perfectly with events: an event will launch from one module and put the message on an eventbus. Every module or application that can connect with the eventbus, can consume those events. This way of working guarantees again that the modules/applications being made are loosely coupled from each other. There are no tight dependencies, they just need to respect the format of the event.

An eventbus can be in memory like the one of Guava: this will typically be used for communication between modules in one application.

It works like a broadcast system: the message being sent will be interpreted by zero, one or many modules that are interested.

The receiver will asynchronously deal with the message and the sender has no idea or need to know this.

In the hexagonal architecture it will typically be the core that will send the events.

The other modules can choose to interact with it or not.

Eventbuses are however most popular as a separate application like RabbitMQ, ActiveMQ, Kafka,…

They work perfectly to communicate between different applications or even the same application that is deployed on several servers.

Conclusion

The Hexagonal Architecture is a very powerful tool to design your applications. It has a lot of support in the community like on Baeldung or in literature like Clean Architecture. I personally enjoyed it a lot, and keep on using it when a project gets complex enough. I hope you enjoy it too!